Here's something nice: I no longer have to strip naked then squat and cough in front of strangers before being permitted a four-hour visit from loved ones. Several prisons in Missouri have started using full-body x-ray machines to see if anyone's trying to secret contraband in or (for whatever reason) out of the institution.

20 August, 2021

Missouri Irradiates Prisoners to Keep Drugs Out of Its Prisons (And I Feel Fine)

13 August, 2021

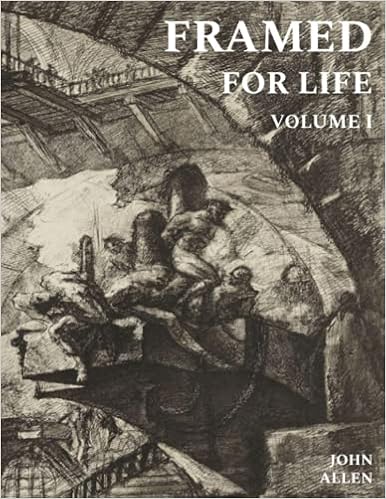

Framed for Life

The latest bit of media about my case came out a few weeks ago – a four-volume book, titled Framed for Life. The author, John Allen, whom I now, in the decade since he published the first book about my case, think of as a good friend, hopes to influence a readership made up of politicians and investigative journalists.

With a scalpel, Allen's

multi-part book dissects my wrongful conviction, showing how Jackson County,

Missouri, prosecutors (now-disgraced Amy McGowan, in particular) committed

fraud on the court in their efforts to convict me of murder. The books not only

expose facts of my trial that were overlooked by virtually everyone, they're

also a scathing indictment of what one judge called Jackson County's

"culture of corruption." Or so I gather; I can't comprehend more than

a few words of them, here and there.

I have copies of the

volumes, generously furnished by the author, and I'm in the process of

reviewing them. The thing is, this is stuff that I've been over and over and

over a hundred times, and can barely assimilate any more. It's as though the

parts of my mind where information about my case, the 1997 death of Anastasia

WitbolsFeugen, is stored have reached maximum capacity. MEMORY FULL,

my brain might as well be saying. I even have a hard time talking about it; it

incites an insidious kind of stress, the physical tells of which are twitchy

eyelids, jaw and neck tension, and the occasional headache.

Nevertheless, I'm

currently picking my way through Volume One of Framed for Life. It's

slow going. This isn't because the book's a mammoth tome (it's actually quite

thin) but because I can only take so much at a stretch before my tolerance hits

its limit and I overload, unable to take in any more about perjury, withheld

documentation, and lies, lies, lies, lies, lies.

It's interesting, if

dismaying, to see old journal entries I made during the year I was held in the

county jail before trial. I can still remember the splintery number-two pencil

dancing uncomfortably in my hand, writing those thoughts in fear but under the

somewhat protective spell of naivete. Those handwritten pages from half a

lifetime ago – those I understand. Their language is unambiguous to me, the

concepts they introduce are familiar in a visceral way.

I wish I could warn

twenty-two-year-old Byron of the pitfalls awaiting him at trial, how stacked

against him the deck is. But I can only sit reading, mute and impotent, as the

travesty plays out on the page. Again.

How many more times will it, I wonder, before this is finally over. It gets so old. Or maybe that's just me, waiting for justice.